Animator Jimmy Murakami dies

Monday 17th of Feb 2014.

The death has taken place of animator and director Jimmy Murakami, an influential figure in animation. He was 80.

Paying tribute, Cathal Gaffney, CEO of Irish animation company Brown Bag Films, said Murakami was "a founding father of Irish animation" and a 'huge inspiration to so many'.

Remembering Jimmy Murakami

March 14th, 2014.

Every superhero has an origin story.

As animators, however, we’re stuck firmly in the human world, but each of us can point to an event that shaped our lives, and pushed us down this path we’ve taken.

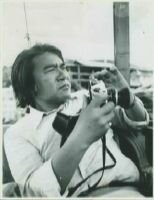

Jimmy Murakami, the great animator/director who led a singular life and died on Feb. 16 at the age of 80, told me of such an event in his life, and his story is so interwoven with the history of America, and strikes such a chord with those of us who love animation, that it must be told.

The story begins on Dec. 7, 1941, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. In the ensuing anti-Japanese hysteria, 120,000 Japanese Americans — many of them, like Jimmy, American citizens — who lived on the West Coast were rounded up and placed in internment camps for the duration of the war.

Jimmy, 8 years old at the time, was sent with his family to the Tule Lake Internment Camp in Northern California. Angry and resentful, Jimmy suffered through freezing winters and baking hot summers. His parents were going through the added agony of watching their oldest daughter — Jimmy’s sister, Sumiko — die slowly of Leukemia. Such was the murderously slow pace of Sumiko’s disease that the camp doctors asked Jimmy’s parents to stop praying that she live, rather they should pray that she be allowed to die and be released from her pain.

It is against this backdrop of physical and emotional hardship, grinding boredom and seething resentment that this story takes place, because every now and then there was a break in the monotony of camp life.

For Jimmy, this was movie night.

On this particular night, Jimmy was excited to see the film scheduled for that evening. Earlier in the day he had been given his ticket, and when the time came for Jimmy and his brother, Jun, to go to the internment camp theater, they set off, walking the mile to where it was. Upon arriving, Jimmy discovered that the ticket he thought he was clutching in his hand was gone. Vanished. Desperate, Jimmy could only retrace his steps, and hope that it hadn’t been ground into the dust by one of the 17,000 inmates of the camp. He must have had a good eye, because after walking for half a mile, Jimmy saw his ticket lying on the ground. He grabbed it, raced back to the theater and watched a movie that he said was the most beautiful thing he’d ever seen.

The movie was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

One can only imagine how those drawings and images washed over an 8-year-old Jimmy Murakami, how ecstatic it was to see that movie at a time when such a fertile and artistic imagination as Jimmy’s needed sustenance and inspiration. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was only five years old at the time, and the legends that worked on the movie – Walt, Milt Kahl, Frank and Ollie, Bill Tytla, the rest of the Nine Old Men, and all the chain-smoking cleanup artists, inkers and painters — probably never imagined that their work would be shown in such a place as Tule Lake, and stir the imagination of an 8-year-old boy incarcerated by his own government.

Those of us familiar with Jimmy’s work know that his artistic sensibilities are pretty far away from the Disney style, but Jimmy knew greatness when he saw it. His response to seeing Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was sheer, unalloyed joy, and it set him firmly on the path where he distinguished himself as an artistic and uncompromising filmmaker.

I suspect Jimmy’s own work has already had a similar effect on children. A whole generation has already seen his twin masterpieces from his collaboration with children’s author Raymond Briggs: The Snowman and When the Wind Blows. Both of these films stay in the mind long after the credits have run, one a bittersweet poem to lost childhood, the other a brutally gentle film about an old couple dying after a nuclear war. It is a legacy Jimmy can be proud of, the origins of which can be traced directly back to a young American boy watching Snow White in an internment camp.

Patrick Gleeson is a veteran of the animation business too, having trained as an animator with Don Bluth on such projects as An American Tail and The Land Before Time. Currently, he is working at Disney TV Animation on the series Gravity Falls.

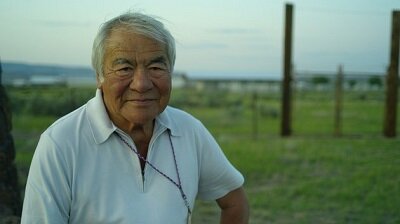

Jimmy Murakami and his wife, Ethna, on the balcony of their apartment in Dun Laoghaire, Dublin, Ireland, in December 2012. Photo courtesy of Patrick Gleeson.

THE MORNING OF A HUNDRED SUNS

Having directed the successful TV special The Snowman, its author, Raymond Briggs, sent me the manuscript of his newly completed book When the Wind Blows. Nothing prepared me for the impact of such a work – so utterly the opposite in content and tone to The Snowman with its theme of friendship and the inevitability of ultimate loss being playfully hinted at.

What I was looking at now was something much less cosy, something indeed shocking in content, and at the same time poignant and heart-wrenchingly sad: the pointlessness of war, in particular nuclear war, and just how helpless we would be in the face of it.

Reading it a second time, I struggled with an unseemly knot in my throat.

But if I were mournful, I was also excited. For this was the subject matter for a film I had long since yearned to direct: a satire on nuclear war. True, a modern audience would have little direct experience of war or the threat of it. And the bête noire of their elders – the nuclear threat – was unlikely, surely, now that Russia and America were no longer at each other’s throats? Might not the story then lose impact? Would a modern audience be moved by a send-up on nuclear war?

It was with considerable excitement the team came together to pull the idea about. For here we had something that had not been done before: an apocalyptic horror about to be animated. Could we ram the futility-of-war message home even harder than the story’s author without resorting to sentiment?

It was a challenging film to make, taking twenty-four months to complete.

But the time did come when I, as Director, and artists, musicians and actors declared ourselves pleased with the final product. When the Wind Blows exceeded all our expectations. Wherever it was screened, critics afforded it rave reviews. It rowed in fiftieth out of a hundred of the best war films ever made. It was rated after Kurosawa’s epic film Ran - I was of course greatly honoured to be in the same company as my favourite director. The Sunday Times declared the film: a visual parable against nuclear war, all the more chilling for being in the form of a strip cartoon.

In 2004, The Hiroshima International Animation Festival kindly invited me to be a member of their jury. The festival featured When the Wind Blows in its program. It was this invitation that afforded me the opportunity to visit the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

I was overwhelmed by the compilation of material.

For hours I read and re-read the documents leading up to the dropping of the atomic bomb. The photographic images showed in disturbing detail this apocalyptic nightmare - the disappearance of a city, the devastation of families and every living thing that stood in the path of the bomb.

That 75,000 people should die – incinerated – in the space of ten seconds seemed beyond imagination. So thoroughly documented was the exhibition one cannot but react with sadness to the tragedy caused by the “Little Boy” bomb dropped on Hiroshima at 8:30 am August 6th 1945. The images were much more hellish than I had expected and have left me with a heavy heart and impressions that have changed the way I view the world.

My visit, in short, rekindled the reaction I had had while reading for the first time When The Wind Blows, and I was convinced of the importance of reminding people - by whatever means - of the senselessness and destructive power of a nuclear bomb, and the untold suffering to survivors.

With tears trickling down my cheeks, I left the Museum. I was somewhat shamefacedly dabbing my eyes when I noticed I had company: a group of European students had also given way to tears.

I returned to my home determined that I would personally continue my quest to make people aware that the future of their children, and of their children’s children, as well as of their planet, was not altogether guaranteed. Although it is a new millennium, the threat of a devastating and `final` war still stalks us.

Is there anything we can do about it?

Jimmy T Murakami

JIMMY MURAKAMI, NON ALIEN at the Irish Film Institute

24 Feb 2010 - 18:30 (90 mins)

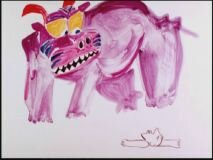

The world-renowned animator Jimmy Murakami (When the Wind Blows, The Snowman) was eight years old when Japan attacked Pearl Harbour during World War Two. Like many other Japanese-American citizens, the Murakami family was evacuated to a concentration camp called Tule Lake in the California desert. Considered a threat to national security, Jimmy’s family, along with many thousands of other internees, spent four years in the camp, where they suffered all kinds of deprivations and where his young sister Sumiko died of leukemia. Jimmy, now in early retirement, decided to return to this period of his life by creating a series of stunning paintings that illuminate his memories of prison life. He also finally chose to return to Tule Lake Camp. Made under the Arts Council’s Reel Art Initiative, Sé Merry Doyle’s wonderful new film follows this extraordinary journey with great compassion and grace.

Director Sé Merry Doyle and Jimmy Murakami will be in attendance at this screening.

JIMMY MURAKAMI, A Brief Overview

Jimmy T. Murakami started his career in animation at UPA Studio, Burbank, California.

Jimmy's travels took him to New York as a director of Pintoff Studio where he worked on the Academy Award nominated short film The Violinist. He also worked for a while at the Toei Studio in Tokyo as consultant director before travelling to London to become the director at TV Cartoons Ltd. It was at TVC that Jimmy co-produced and directed the British Academy Award winning film Insects.

Back in Los Angles, Jimmy set up Murakami Wolf Films where he produced the Academy Award nominated film Magic Pear Tree.

Jimmy now lives in Dublin, Ireland, where he continues to produce and direct animated shorts, TV series and feature films. Amongst the film he as worked on are TVC's When the Wind Blows (director) and The Snowman (supervising director).